| Disclaimer: While this article highlights some negative views on the economy and stock market, I am not necessarily endorsing market timing for all or any investors. It is a very difficult strategy to execute successfully. In addition to developing a reliable model to time markets, patience (or lack thereof), tax frictions (i.e., capital gains), and other issues make market timing an especially challenging endeavor in practice.

As with most investment decisions, one should assess a variety of factors relating to markets as well as their own risk profile and investment portfolio before attempting to execute such a strategy. Please contact me to discuss the risks and suitability of these or other investment strategies. |

| According to Investor’s Intelligence, bullish sentiment among investment advisors recently hit a 30-year high. Moreover, consumer confidence is now its highest level in 16 years. How did markets perform back then around 1987 and 2001-2002? Hint: Not well!

Bullish sentiment often translates into easy money. In turn, this can enable elevated market valuations as well as the survival and growth of many enterprises that would otherwise fail or stagnate. However, once the easy money dries up, corporations are left to fend for themselves and some will collapse. Share prices tend to follow. This article looks at US corporate cash flow trends. I observe both the money flowing into companies as well as how they are allocating it. My research indicates easy money is drying up and companies are increasingly getting squeezed for cash. Given the backdrop of investor optimism and elevated valuations, I believe we have the right the ingredients for a significant market correction. |

Figure 1: American Corporate Cash Squeeze

Source: Aaron Brask Capital

Overview

This article looks into cash flow trends of US companies. My purpose is to draw some conclusions about the current state of corporate fundamentals and, by extension, the stock market. The first section explains why I believe this analysis is useful at this point in time. I present some intuition alongside some historical context.

The next section highlights the actual cash flow trends. I first observe the cash going into corporations. This includes capital raised (e.g., debt and equity) and revenue. I then look at how cash is being allocated via dividends and buybacks.

Why Does This Matter?

The reason I believe corporate cash flow trends are important is because they provide a useful lens for looking beneath the surface of market prices. While it is important to look at fundamentals, companies can employ a variety of accounting techniques and metrics (e.g., earnings per share) that can obscure their true performance. Accordingly, it can be helpful helps to follow the money. Indeed, the presence or absence of cash flows ultimately comes to the surface despite even the most sophisticated accounting manipulation.

Cash flow analyses can be especially important in an environment of elevated market valuations and sentiment when investors are not paying much attention. As I have highlighted in previous articles (see The Non-credit Crisis and More Market Correction to Come), market prices are currently elevated well above their fundamentals. Moreover, investors and broader consumer sentiment are hitting highs[1] not seen since previous bubble periods.

In an atmosphere like this, CEOs and CFOs presumably do not want to stand out in a negative light. If there is bad news to report, they may prefer to save face by taking a more anonymous approach whereby they do whatever they can to stall the reporting of bad news until everyone else is doing it. For example, FactSet figures indicate non-GAAP earnings-per-share figures (which allow some discretion) are 25% higher than the GAAP figures for Dow Jones Industrial companies in Q3 2016. This corporate mindset can lead to an eventual catharsis where many corporations get their skeletons out the closet at once.

Think back to the tech bubble. Investors were focused on financial metrics like eyeballs and clicks instead of cash and market valuations. Many of these tech (and other) companies would not have sustained as long as they did if it were not for the easy money that came along with the euphoria. Barron's timely ‘Burning Up’ article in March 2000 highlighted a lengthy list of companies burning through capital at alarming rates. Without doubt, this article challenged the credibility of the extremely positive sentiment and elevated valuations at the time.

Unfortunately, the easy money spigot was left open far too long. As investors sobered up, corporate defaults mounted, valuations came back down to more reasonable levels, and the NASDAQ index ultimately plummeted by 83% over the next few years.

During the tech bubble, many of the problems were concentrated in the TMT (tech, media, and telecom) sectors. Their nosebleed valuations stood out from the rest of the market. During the credit crisis, banks and housing companies absorbed much of the blame. This made both bubbles more obvious (even if in retrospect). The current bubble is different.

Widespread overvaluation (presumably due to central bank efforts) makes this bubble less conspicuous. In fact, I like to call this a stealth bubble. The prices of virtually all assets are elevated and some people are calling this the ‘everything bubble’. I suspect it is easier to miss everything bubbles since our brains are wired to think in relative rather than absolute terms[2].

To be fair, some have argued the brick-and-mortar retail sector is under assault. For example, Business Insider just wrote about America’s retail apocalypse. However, articles about cash burn and financial stress (e.g., Tesla, Sears, GoPro, Netflix, and Uber) do not appear relegated to a particular sector. Whether or not it there is a sector that is particularly vulnerable, this article will shed light on the broader cash flow trends for the market in aggregate.

| Note: Bubbles can become bigger bubbles and last a long time!

While elevated valuations may set the stage for dismal returns over the longer term (e.g., decade), markets and valuations can remain extended for years before a correction takes place. During the run-up to the tech bubble, many value-based investment managers suffered poor returns relative to the broader market. At one point, Barron’s Magazine questioned Warren Buffett’s expertise in their What’s Wrong, Warren? article. Yale professor Robert Shiller pointed out the extreme market valuations in his book Irrational Exuberance (published March 2000) just before the market collapsed. However, Shiller also published a second edition of this book in 2005 in which he forewarned of the real estate bubble. While this was well before the ensuing housing crisis, he was also clear to point out that the bubble could continue for some time before it ultimately popped. Shiller was not alone in identifying the real estate bubble. Multiple storylines in The Big Short highlighted the seemingly uncanny ability of the housing bubble to persist. This has been the case throughout history and partly explains the famous quote from British economist John Maynard Keynes: “Markets can remain irrational for longer than you can remain solvent.” My point is simply that bubbles can sustain for long periods. Even when the writing is on the wall, investors tend to look the other way until something forces their hand. Ultimately market prices follow the fundamentals and the reconciliation is often violent. |

Incoming Cash Flow Trends

Below I analyze the cash going into US companies. The first section highlights the capital being raised by companies and the following section discusses their revenues and profits.

Capital

Many companies raise capital by issuing new stock and debt (and some hybrid securities). Looking at the trend for US equity issuance in Figure 2, we see there has been a clear decline over the last two years. That is, there is less money flowing into US companies from issuing equity. To be fair, the extremely low interest rates provide an attractive opportunity for raising debt capital. So we analyze this trend next.

Figure 2: US Equity Issuance ($bn)

Source: Aaron Brask Capital, SIFMA

Looking at the figures for debt in Figure 3 below, there has been a trend toward less since issuance reached its peak shortly after the Federal Reserve’s quantitative easing programs ended in late 2014. While the one-year moving average shows the broader trend and adjusts for seasonality, the most recent data point from Q3 2016 indicates a net redemption of debt. In other words, what once was a source of cash for these companies previously was actually a drain during this period.

Note: The data for equities above are for all US companies but the data for debt only reflects non-financial companies. Moreover, the debt data reflects total outstanding debt and thus reflects redemptions as well. The equity data only reflect issuance but we address buybacks in a later section.

Figure 3: Net Debt Issuance for US Non-Financial Companies ($bn)

Source: Aaron Brask Capital, Federal Reserve

On balance, I would expect companies to be eager to borrow or issue stock given the still low interest rates and elevated stock valuations. Based on this notion, it is tempting to speculate that a lack of investor demand is driving this trend.

Sales

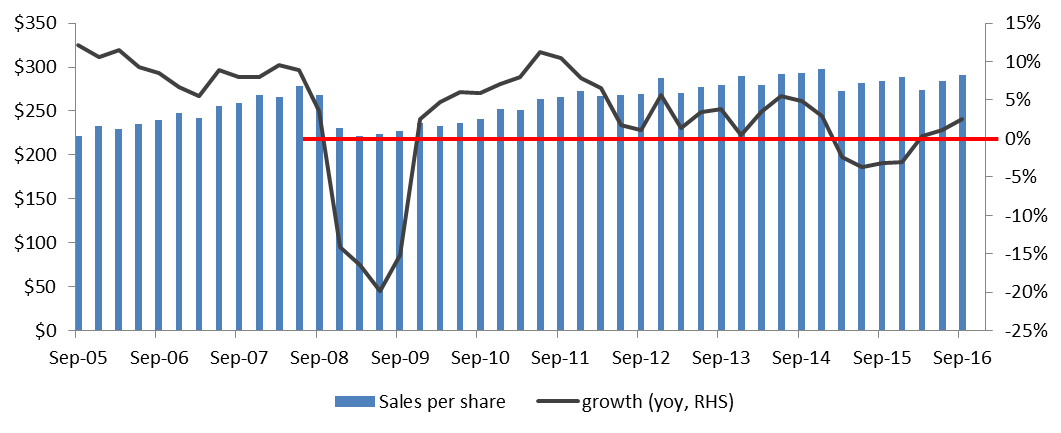

In addition to raising capital, companies naturally earn revenues. Figure 4 indicates revenue growth has been lackluster in recent years. While some of this was due to issues in the energy sector (e.g., oil price collapse), growth still has not recovered to the average levels seen in prior years.

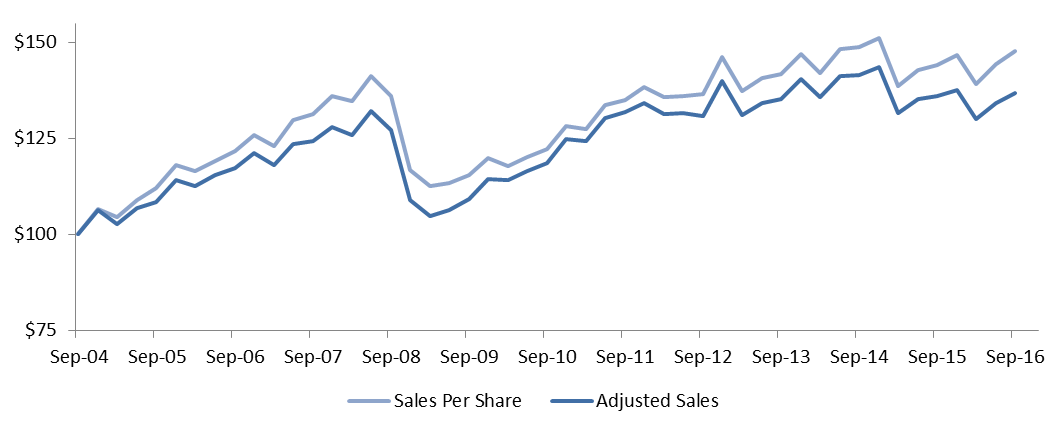

Figure 4: S&P 500 Sales per Share

Source: Aaron Brask Capital, Y-Charts

Figure 4 above shows per-share figures. This includes some financial engineering in the sense the numbers of shares outstanding has decreased. In Figure 5 below, I adjust for the reduced shares outstanding (by multiplying by the divisor) and reset both figures to start at $100. This adjustment amounts to an 8% differential over the 12-year period. In annualized terms, the per-share growth was 3.3% per year whereas the adjusted growth was 2.7% per year. While this difference may appear small, it is relevant to the ultimate cash that is retained by companies since profit margins are generally higher for each marginal dollar of sales.

Figure 5: Adjusted S&P 500 Sales per Share

Source: Aaron Brask Capital, Y-Charts

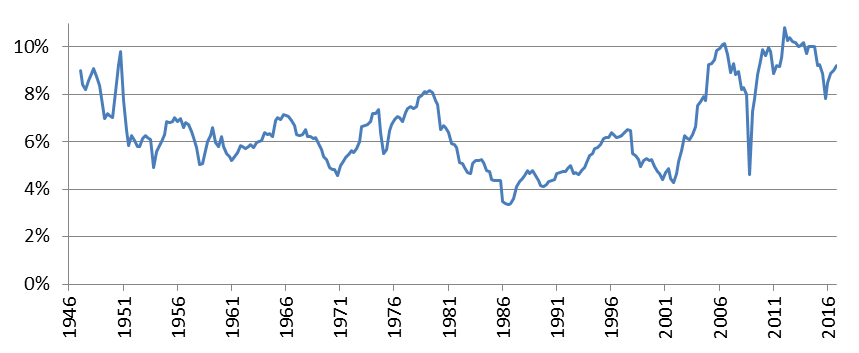

In addition to the lackluster revenue growth, profit margins also appear elevated. They are sitting near the high end of their historical range around 9%. If margins revert back to the 6.5% average seen over the last 70 years (i.e., post-war era), we would see a 27% contraction in profits.

"In my opinion, you have to be wildly optimistic to believe that corporate profits as a percent of GDP can, for any sustained period, hold much above 6%.

|

Figure 6: Profit Margins (profits after-tax as % of GDP)

Source: Aaron Brask Capital, Federal Reserve

On balance, the above figures indicate US companies may be experiencing significant pressure from a cash flow perspective. Moreover, the uninspiring revenue growth coupled with elevated profit margins could exacerbate this pressure. Based on these trends, something must give on the other side of the equation. That is, US companies must be making some reductions within their corporate allocation strategies. I discuss precisely this in the next two sections.

Corporate Allocation (Outgoing Cash) Trends

It is interesting to note that companies are at the mercy of investors, capital markets, and consumers for the incoming cash flows we discussed in the previous sections. However, this is not the case with their allocation strategies. While they naturally must spend money on labor, materials, and other overheard, they naturally have a choice in how they allocate cash (including but not limited to profits) to dividends and buybacks. Below I discuss the dividend and buyback trends of US companies[3]. I believe these choices are indicative of their financial situation as I discuss here.

Dividends

Many investors prefer to buy dividend-paying companies. Moreover, some only want consistent and increasing streams of dividends. Accordingly, companies typically only cut dividends as a last resort as they know it sends a definitively negative signal to the market.

Figure 7: S&P 500 Dividends per Share Growth (yoy)

Source: Aaron Brask Capital, Y-Charts

Dividend growth rates have been slowing in recent years. While there have not been any cuts, data indicates a recent dividend growth for the S&P 500 has come down below the 5% level. To put this into context, this level is just below the average rate of 6% over the last 30 years[4]. However, the last time dividend growth slowed to this level was Q2 of 2008. This was just before the market fell by 46% (after it had already slipped 17% from its 2007 high). The time before that was in the late 1990s. During that period, dividend growth stabilized around 5% for a few years before it headed south again and the tech bubble burst. I suspect the reason this below-average dividend growth did not fall sooner at the time was because investors were preoccupied with the new eyeball, click, and other metrics and less focused on cash.

If dividend growth continues along its current trajectory, then growth will soon turn negative (i.e., aggregate dividends for the S&P 500 will be cut). In my view, this would not be taken well by investors. Given the backdrop of bullish sentiment and elevated valuations, a tangible negative event like this would likely catch investors off-guard and trigger significant selling as risk appetite swiftly turned to risk aversion.

Buybacks

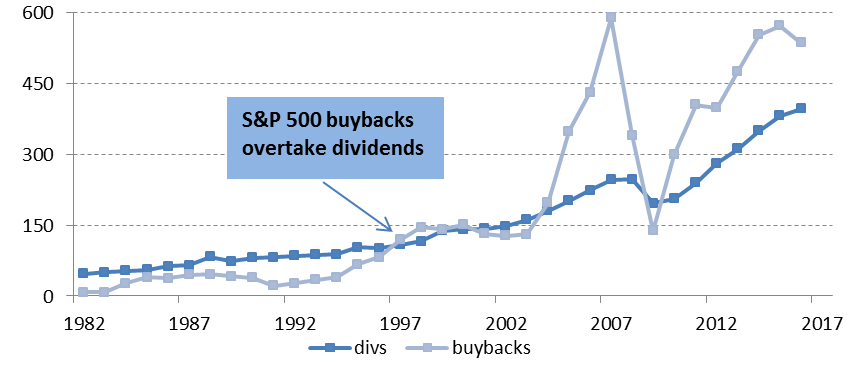

Buybacks represent an alternative method to pass money back to shareholders. The idea is to increase the percentage ownership in the company for ongoing shareholders by reducing the number of shares outstanding. All else equal, fewer outstanding shares translate into higher per-share figures for sales, earnings, dividends, etc. In addition to these fundamental benefits, the buying activity may also provide support to share prices.

S&P 500 companies have actually allocated more money to buybacks than dividends in recent years. In 2016, S&P 500 companies repurchased $536 billion of shares and paid $397 billion of dividends. That is, 35% more money has been allocated to buybacks relative to dividends. This was not always the case, though. S&P 500 companies allocated twice as much to dividends relative to buybacks in the early 1990s.

Figure 8: S&P 500 Dividends versus Buybacks ($bn)

Source: Aaron Brask Capital, Credit Suisse

While some claim buybacks are a more tax efficient way of returning capital to shareholders (since dividends are taxed), my skeptical side suspects corporate executives also appreciate the less visible nature of buybacks. That is, they can reduce their allocations to shareholders without necessarily sending the negative signal of a dividend cut. As Figure 8 indicates, buybacks overtook dividends sometime in the mid-90s and have clearly experienced more allocation volatility since then.

Given the increasing popularity of and attention to buybacks, corporate CEOs and CFOs are likely aware of potential signals their buyback strategies send to investors. However, reducing buybacks is still much less visible move than cutting dividends from a market signaling perspective.

Looking at the buyback figures, the trend is decidedly more negative than it is for dividends. Figure 9 (from FactSet) below shows the steep drop in both the number of companies repurchasing shares and the total amount. Again, some of this could be related to the issues in the energy sector. However, the last time buybacks fell this significantly two quarters in a row was in early 2008.

Figure 9: S&P 500 Buybacks ($bn)

Source: Aaron Brask Capital, FactSet

Standard and Poor’s (S&P) recently released their preliminary figures for Q4 2016. While there was a significant rebound in buybacks relative to Q3 2016, the figure was still lower than Q4 2015. Even when taking out energy (which saw the largest reductions), buybacks for the rest of the index still contracted by 6% when comparing the Q4 periods.

Fewer buybacks will lead to less growth for commonly reported per-share figures. However, this impact is slowly revealed as lower growth over the longer term. That is, the impact is not necessarily immediate. To put buybacks into another perspective, I know consider their contribution to market volume.

Buyback activity has neared $600 billion in recent years and the monthly dollar-volume on the New York Stock Exchange is typically just under $1 trillion. Assuming approximately half of this volume is high-frequency traders, I estimate buyback activity is equivalent to approximately one month’s worth of volume.

In other words, reduced buyback activity could be a double-whammy. On the one hand, reduced buybacks could be indicative of the underlying financial distress. However, if this stress translates into material selling, there will be fewer buyers present to absorb the flow.

Conclusions

The backdrop of record high sentiment and elevated valuations likely makes markets vulnerable to any bad news. Unlike previous bubbles where the troubles were concentrated in particular sectors, central bank efforts have pushed up prices across virtually all assets. With no particular trouble sector standing out, I liken the current situation to that of a stealth bubble.

Many investors appear to have their heads stuck in the ground right now. As I have highlighted in my previous articles (see The Non-credit Crisis and More Market Correction to Come), valuations matter over the longer term. Indeed, my preferred metric for overall market valuation has a greater than 90% correlation with returns over the next 10-12 years. However, we live in real-time. So it is difficult to see such long-term trends. Unfortunately, my research indicates a correction of 40% or more is likely given current valuations.

As always, timing a market turn is notoriously difficult – especially at tops where there is no well-defined bound (see More Market Correction to Come). Just think about trying to predict when an alcoholic will sober up or where a really rotten drunk might fall over in a parking lot. With markets, crowd psychology comes into play. While investor confidence is currently at highs, we know from history it can turn on a dime.

The recent trends in capital raising (issuing debt and equity) and corporate allocation strategy indicate potential stress within corporate America. In particular, the reduced growth rates in dividends and reductions in buybacks are eerily similar to the situations preceding the two last major market corrections (i.e., technology bubble and credit crisis).

To be clear, I am not claiming any of these cash flow trends will necessarily be the catalyst for the next correction. Indeed, there are a variety of situations in play that could get investors to reconsider their optimism (e.g., our new president, China, or Brexit/Europe). Notwithstanding, these trends are not encouraging and, in my view, suggest it is a time to sensibly reduce risk.

The appropriate actions to take are different for each investor. It naturally depends on each investor’s overall risk profile and financial situation. Some investors may wish to maintain their current positions but divert any income to safer investments (e.g., short term government bonds). Others may prefer to reduce as much equity exposure as possible without incurring capital gains taxes. Indeed, taxes naturally must be considered when adjusting one’s portfolio. Long-term positions with low basis may result in significant capital gains taxes. The certainty of taxes could outweigh the risk of a market correction. However, the cost of changing allocations may only amount to the transaction costs for buying and sell (i.e., no tax friction) for investments held in tax-deferred accounts (e.g., IRAs).

Even when the data or numbers strongly indicate one particular strategy is appropriate, each investor has their own unique investment experiences and perspectives. As strongly as I believe markets are ripe for a correction, it can be agonizing to watch markets go up from the sidelines and this is a real possibility. As such, it is important to balance the pros and cons of any investment strategy with the risk profile of each investor – especially when those strategies involve market timing.

Please contact me to discuss the optimal approach for adjusting your portfolio to reflect these or other views. I can help you assess your risk profile and balance the risk/reward tradeoffs (including potential tax implications) of altering allocations.

About Aaron Brask CapitalMany financial companies make the claim, but our firm is truly different – both in structure and spirit. We are structured as an independent, fee-only registered investment advisor. That means we do not promote any particular products and cannot receive commissions from third parties. In addition to holding us to a fiduciary standard, this structure further removes monetary conflicts of interests and aligns our interests with those of our clients. In terms of spirit, Aaron Brask Capital embodies the ethics, discipline, and expertise of its founder, Aaron Brask. In particular, his analytical background and experience working with some of the most affluent families around the globe have been critical in helping him formulate investment strategies that deliver performance and comfort to his clients. We continually strive to demonstrate our loyalty and value to our clients so they know their financial affairs are being handled with the care and expertise they deserve. |

Disclaimer

|

- See CNBC and Reuters. ↑

- See the work of Dan Arielly or Richard Thaler. ↑

- Capital expenditure (capex) is also relevant. However, most companies do not report maintenance versus growth, so it is difficult to interpret total capex figures. Having said that, annual (up to Q3 2016) capex for S&P 500 ex-financials fell by 9% (+2.4% growth removing energy as well). Assuming the 2016 figure is also down, this makes five consecutive years of capex declines. ↑

- I use the last 30 years because buybacks were less prevalent before and this makes the figure more comparable to the current environment. ↑