| For many endowments, foundations, and other investors, a steady income stream is lifeblood for their investment strategy. On one hand, we are fortunate our markets offer a wide variety of securities (e.g., stocks and bonds) providing precisely this. Indeed, there is a long list of companies with extensive histories of paying and increasing dividends – many of which are likely to continue (Page 5, Figure 7) – and there is an even longer list of highly rated bonds that will pay steady streams of fixed income. On the other hand, it is unfortunate many funds and portfolio managers effectively destroy what would otherwise be steady income streams as their investment strategies treat income as an ancillary concern at best.

We explain this unnecessary income instability and provide examples from some of the largest and most reputable investment funds. We also discuss three primary drivers of this phenomenon: myopic focus on total return, unintended consequences of investment mandates, and advisor over-reliance on statistical models. Our Solutions section describes simple strategies that make steady income the top priority. Based on the pillars of quality and value, these strategies focus on income and provide a robust foundation for capital preservation and growth. They also facilitate a higher degree of transparency and should thus deliver more peace of mind to retirees and other investors. |

The Problem

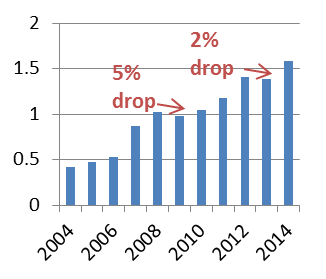

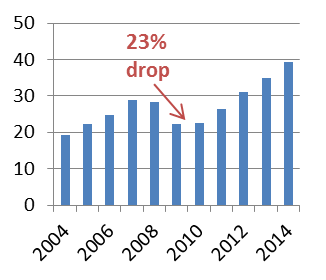

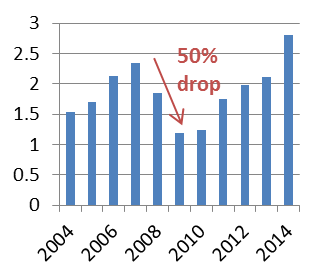

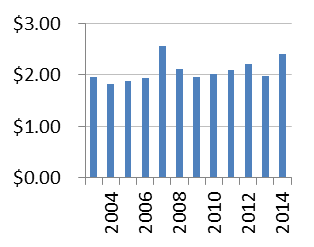

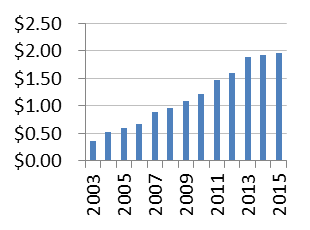

There is strong demand for steady income streams. However, most investment products and strategies fail dismally in this regard. How do they destroy steady income streams and why would anyone do such a thing? We discuss the reasons why in the following section (Primary Drivers) but first illustrate the nature of the problem here. Observe the increasing instability in dividend distributions from left to right in Figure 1. All else equal, income-focused investors should prefer the steadier income streams if they were aware of the disparity.

| High Quality[1]

|

Broad US Equity Market[2]

|

Large ($50+bn) Mutual Fund[3]

|

Source: Aaron Brask Capital

| Note: We intentionally footnoted the names of the actual benchmarks as our goal is not to disparage any particular fund, but rather to illustrate our point: even some of the best and most successful funds inject unnecessary volatility into their income profiles. |

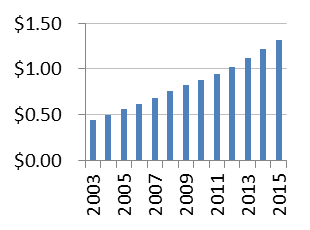

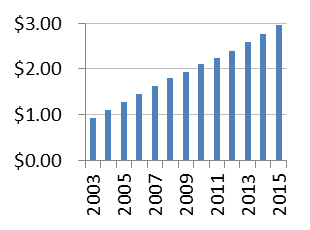

Starting on the left in Figure 1, we first look at the dividend history of higher quality stocks. While we are confident in our ability to construct better models for quality, we used a history of paying increasing dividends as a proxy for quality (as defined by the NASDAQ Dividend Achievers Select Index). Paying dividends is generally acknowledged as a positive attribute in terms of quality and increasing dividends even more so. The middle and right charts show the dividend histories of the broad market (as defined by the S&P 500 index) and the renowned Dodge and Cox Stock Fund, respectively.

While each of the above portfolios suffered declines in their dividend income, the quality portfolio experienced the smallest decline in dividends and highest growth. Dividends fell less than 5% peak to trough during the credit crisis and grew at an annual rate of 9%. Overall, the simple litmus test of historically increasing dividends resulted in a more reliable and faster growing income stream relative to the broad market. The broad market’s dividends suffered a decline of more than 23% during the credit crisis and the average annualized growth over the decade was just 7.3%.

These results should not be surprising. Taking the market as a whole imposes no controls for quality or dividends; one simply invests in the good, the bad, and the ugly. We discussed the impact of quality more generally in our article on article index Investing. We arrived at the same conclusion here as we did with overall returns: quality has a positive impact on investment performance.

The Dodge and Cox Stock Fund suffered the worst decline in dividends by far as they fell by almost 50% during the credit crisis. We should note they also distributed some capital gains over this period. Including these gains actually made the income stream more volatile so we narrowed our focus to just the dividend distributions.

Figure 2: Dividend Statistics

| High Quality | Broad US

Equity Market |

Dodge & Cox

Stock Fund |

|

| Maximum dividend drawdown | -5% | -23% | -49% |

| Average growth | +9% | +7% | +6% |

Source: Aaron Brask Capital

It is worth noting declines in dividends do not necessarily imply dividends were cut. In the case of our broad market index where there is minimal turnover, dividend cuts were indeed the driving factor behind reduced dividends. However, in a more active (higher turnover) fund it is possible the portfolio was rebalanced to include companies paying lower or no dividends. For example, a fund might have sold a dividend paying stock like Coca Cola to purchase a growth stock paying no dividends like Google or Berkshire Hathaway.

It is also worth noting the quality portfolio we used as a proxy has performed mostly in line but slightly better than the broad market over this period. The Dodge and Cox Stock Fund underperformed both by more than 20%. As a result, this fund delivered lower returns and a more volatile dividend stream over this period.

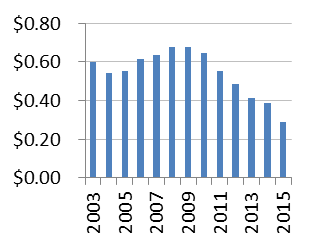

Figure 3: Income Profiles of Other Prominent Stock Funds

| American Cap. Income Builder

|

Templeton Growth

|

T Rowe Price Equity Income |

Source: Aaron Brask Capital

Skeptical readers may wonder if we cherry-picked this fund to prove our point. This was not the case. We looked at many of the largest and most respected equity fund companies. They all exhibited similar if not worse results (see Figure 3 above and Figure 4 below). While it is not the point of our articles, it is worth noting all three of these funds also significantly underperformed the broad market over the last 10 year periods. Notwithstanding, there are instances where these funds can generate value for their investors above and beyond their fees. For example, the Dodge and Cox Stock fund skillfully navigated the dot-com bubble by adhering to their disciplined value-based investment process. However, this outperformance is not the norm and even if we ignore overall underperformance, these and other funds simply do not deliver steady income profiles.

| AmCap Income Builder | Templeton Growth | T Rowe Price Equity Income | |

| Maximum dividend drawdown | -24% | -52% | -34% |

| Average growth | -4% | +9% | +2% |

Source: Aaron Brask Capital

The truth is simple in our view. Dividends are an indicator of quality. Purchasing higher quality (e.g., increasing) dividends at attractive prices (i.e., higher dividend yields) is a form of quality-based value investing – a highly respected and historically successful strategy. Strategies that ignore dividends or treat them as an ancillary concern may be actively straying from quality and/or value. As such, they leave the door wide open for volatile income streams and underperformance.

A Quick Word on Bonds

Our discussion up to this point has focused on stocks and dividend income. While we will not go into as much detail, we will highlight a few relevant points in the context of bonds as they are one the simplest investments and comprise the core of many portfolios.

Consider a situation whereby a borrower receives money from a lender, agrees to pay interest on that loan, and then repays the principal back to the lender at a pre-specified later date. Assuming the borrower poses minimal credit risk, the lender will receive a fixed stream of income[4]. The sanctity of bonds as low-risk and fixed-income investments is predicated on this contractual obligation to provide a stable and predictable stream of cash flows in exchange for an upfront investment (whether a bond is purchased at par or not).

Unfortunately, the benefits of this relationship are compromised when one starts to sell bonds before they mature. In particular, active portfolio managers who jump from one horse to another – presumably jockeying around to improve overall returns – may be diminishing the true value bonds deliver as low risk investments.

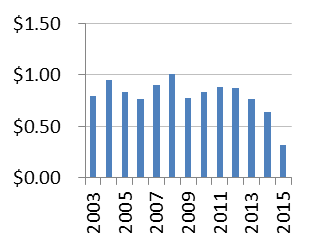

We are the first to acknowledge we are not experts in bonds or fixed income investing. Moreover, we do not have the data to conduct the same analysis we did for equities. However, after looking at the income profiles of several prominent fixed income funds, it seems to us fixed-income funds suffer from the same phenomenon. Moreover, the problem is compounded with the reinvestment of expired or called bonds at different interest rates.

Figure 5: Income Profiles of Prominent Fixed-income Funds

Dodge and Cox Income Fund |

Templeton Global Bond |

Loomis Sayles Bond Fund |

Source: Aaron Brask Capital

Our view is that bonds are typically used to reduce overall market volatility in a portfolio. In exchange for reducing market risk, one foregoes the growth potential with equity investments. The lower volatility nature of bonds also translates into less opportunity. Indeed, both the underlying fundamentals and market prices are significantly less volatile than those of their equity counterparts. David Swensen (the legendary portfolio manager of Yale’s endowment) makes this point repeatedly in his books and lectures. Less volatility naturally leads to less opportunity. Accordingly, he focuses the majority of his efforts in finding managers in more volatile asset classes such as stocks.

So let’s add this up. If the primary utility of bonds is to risk reduction (not growth) and bonds offer less opportunity to profit from buying and selling, we feel this makes a strong case for passively managed bond portfolios. Moreover, if we consider the income streams, the case is even stronger as portfolio managers are likely to ignore the income profile in search of higher total returns just as they do with stocks.

The Importance of (Income) Stability

Watching portfolio market values move around is one thing. It makes some nervous but at the end of the day should not impact larger decisions if the volatility is tolerable (i.e., compatible with one’s risk profile). While we hope we are stating the obvious, aligning investment portfolios with investor risk tolerance should be a key element of every advisor’s financial planning services.

Bigger problems occur when one’s income stream is less reliable – especially for those relying on investment income for their budget (e.g., retirees). Anyone relying on dividends for income will naturally prefer a steady and growing trend versus a more volatile stream of cash flows. Depending upon one’s financial profile, stability of investment income can be anything from a non-issue to lifestyle-critical matter. We illustrate this by considering four different scenarios with varying dependence on the portfolio’s income. In particular, we view risk through the lens of risk to required income.

Figure 6: Varying Degrees of Dependence on Investment Income

| Scenario | Description | Dependence |

| 1. Portfolio income >> budget | Portfolio generates significantly more than enough income for spending budget. Dividend cuts unlikely to result in accessing principal. | Low |

| 2. Portfolio income ≈ budget | Portfolio generates income approximately equal to spending budget. Stable versus volatile dividends is a critical determinant of whether spending principal is necessary or not. | High |

| 3. Portfolio income < budget | Portfolio generates slightly less than spending budget. Less stable dividends will result in higher rate of principal access and accelerate principal erosion. | Moderate-High |

| 4. Portfolio income << budget | Portfolio generates significantly less than spending budget. Income is less relevant as principal will like be spent and depleted. | N/A |

Source: Aaron Brask Capital

Depending upon the risk-based framework one utilizes, instability of investment income in each of these situations may impose various decisions regarding asset allocations and spending budgets. Getting over the hurdle of accessing principal to make up for budgetary shortfalls is a significant milestone for any investor or entity as it allows one to live off of the interest (and/or dividends) and extend the longevity of one’s wealth. Fortunately, many investors who cannot yet live off of the interest of their portfolio alone can restructure their portfolio and effectively upgrade their situation from scenario #3 to #2 or from #2 to #1. We discuss this particular strategy at the end of the Solutions section.

Generally speaking, accessing principal as a means to fill a budget shortfall makes one dependent on market prices and this naturally introduces volatility into the process. Whether the assets are supporting an endowment, foundation, or individual retiree, this can lead to a very slippery slope whereby less principal translates into less income and accelerating shortfalls. This is dangerous route as one’s dependence on market movements increases and hope displaces strategy.

This logic argues for establishing a steady and growing baseline of dividend income to minimize dipping into principal. It is worth highlighting that instability can lead to a buy-high / sell-low strategy that lowers overall returns and can accelerate portfolio depletion. Given the positive correlation between markets and dividends, investors reliant on accessing principal may find themselves digging deeper into principal at the worst times (i.e., selling more when market prices are depressed). The converse is also true as less principal will be accessed (or more excess income will be reinvested) during bull markets when prices are higher and dividends are rising. This phenomenon is revealed in the example and simulations we discuss later (Driver 3 of Income Volatility). The good news is that we discuss strategies to circumvent this issue in the Solutions section.

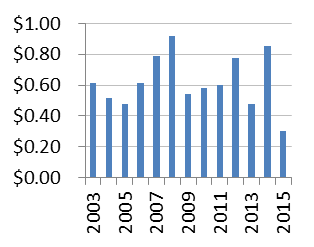

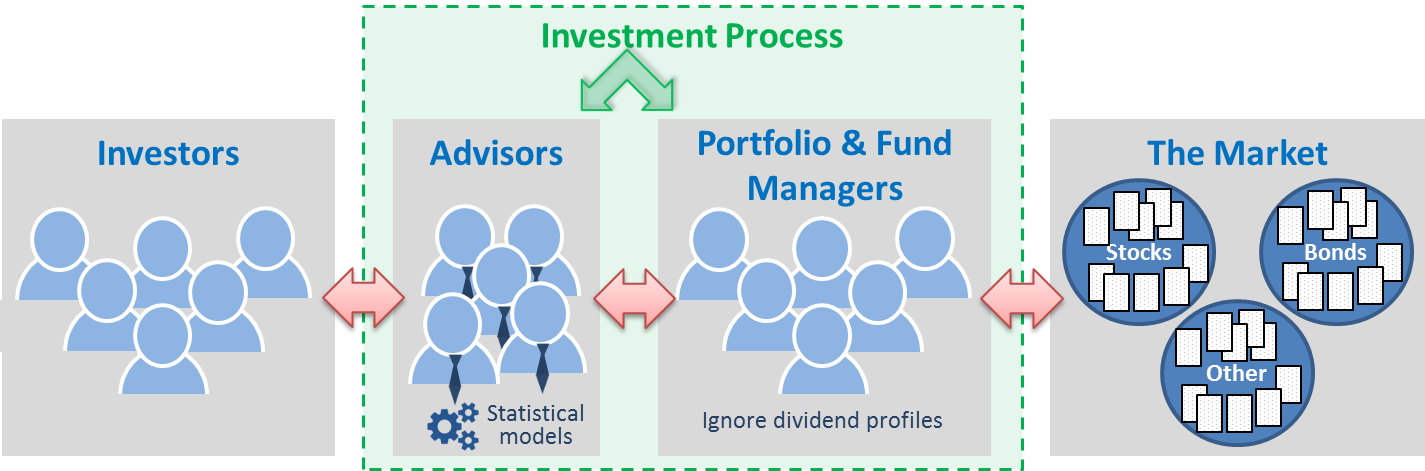

Income Volatility: Primary Drivers

So there is a vast array of steady income-producing securities (Figure 7 below provides some examples), but intermediaries somehow inject volatility into the income profiles of the end-products. Moreover, the income volatility can results in varying degrees of consequences for different investors. Why would anyone do this? This section highlights what we believe are the three primary factors behind this phenomenon. The next two sections explain why we expect this income instability issue to persist and suggest solutions.

Figure 7: Income Profiles of High Quality Stocks

Coca Cola |

Johnson & Johnson |

Proctor & Gamble |

IBM |

Walmart |

CVS |

Source: Aaron Brask Capital

Driver 1: Myopic Focus on (Total) Returns

It should come as no surprise returns are the top priority for active managers; it is the number one yardstick by which they are measured. Their returns are calculated as total returns. They account for both the price appreciation as well the dividends paid to shareholders. Regardless of what shareholders actually do with their dividends, they are assumed to be reinvested in the total return calculation. These return calculations make absolutely no distinction between stable or volatile dividend streams.

Given this focus on return, active managers typically view their duty as beating a benchmark index. This is how they attempt to earn their higher fees. Inaction is not an option (otherwise they would be a passive portfolio), so they regularly purchase stocks they expect will appreciate more than those they own. In this quest for return, active managers tend to ignore the impact their strategy has on the dividend income of their fund or portfolio.

In the context of indices and passive management, the same notion applies. Index rules are typically chosen based on a combination of theoretical sensibility and historical backtesting. However, just as with active managers, performance is measured by the total returns and the income stream is rarely if ever considered. As we discuss in the next section with Driver 2, there are dividend-related indices but they do not explicitly address income stability. The result is precisely what one would expect – a volatile stream of dividends.

Driver 2: Unintended Consequences of Investment Mandates

While most funds naturally focus on returns as the core mandate, the growth of passive investing has led to another class dividend-based indices and products. These products are primarily based on one of two dividend strategies. The first and more popular strategy focuses on dividend yield. The second strategy focuses on companies who have histories of growing their dividends. Unfortunately, neither of these dividend-based strategies is geared toward achieving a stable income stream.

The dividend yield strategies naturally focus on companies with higher dividend yields. This approach is generally viewed as a naïve value investment strategy. Indeed, the high dividend yields indicate low valuations but often indicate distress as well. This is especially true when the yields are extremely high. For example, consider a company that paid dividends over the last year but more recently ran into significant issues (bank stocks during the credit crisis come to mind). The share prices generally fall due to the bad news. Accordingly, the reported (trailing) dividend yield will be higher but indicative of the distress.

If there was no distress and companies continued to pay (and perhaps increase) their dividends, then the dividend stream of high dividend yield portfolios would monotonically increase. However, this is not the case. Let us take the Vanguard High Dividend Yield ETF as an example. This ETF paid an annual dividend of $1.56 going into the credit crisis, but many of these dividends were cut resulting in an annual dividend of $1.08 just 18 months later – representing a cut of just over 30%. For comparison, the dividends of the broad market were cut by 23% over the same period. In other words, the quest for higher yields ultimately led to a more volatile income stream due to the correlation between high dividend yields and distress.

The second class of dividend-based ETFs typically identifies and invests in companies with sufficiently long histories of growing dividends. As we discussed in the first section, this is a great recipe for identifying higher quality companies. However, these indices do not pay attention to the price paid to purchase these higher quality companies. In particular, they may replace or rebalance existing holdings with companies paying lower dividend yields. This can have a significantly negative impact on the dividend stream.

Consider Coca Cola (KO) in the late 1990s as one example. Naïve strategies focused solely on strong histories of dividends would have purchased KO with no regard for dividend yield (or more generally valuation). However, KO bizarrely got caught up in the tech bubble and was trading at sky high valuations with price-earnings ratios exceeding 50. Its dividend yield was just 0.67%. For comparison, 3M’s (MMM) dividend yield was almost four times higher than Coca Cola at the time. Investing in MMM instead of KO would have resulted in significantly more income and capital appreciation for years to come.

In our view, the lesson to be learned from these dividend-based strategies is that quality and dividend yield (valuation) should both be considered if one wishes to construct portfolios with more reliable income profiles. More generally, we view this as just another symptom of a larger problem whereby the investment industry manufactures flavors to suit all tastes. They manufacture products based off of a wide variety of individual factors and ignore the significant benefits achieved by sensibly combining multiple factors. Marketing seemingly trumps quality as the industry caters to advisors and their sales pitches instead of investors and performance.

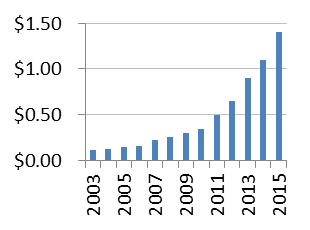

Driver 3: Advisor reliance on statistical versus natural income models

Over the last 100 years, the proliferation of pooled investments such as mutual funds and ETFs has contributed to a bifurcation of the investment process. On the one side, there are financial advisors who interact with investors. On the other side, there are portfolio and fund managers who ultimately invest money into individual securities. The advisors effectively intermediate between portfolio managers and investors. As Driver 1 illustrated, there are natural explanations for portfolio managers’ ignorance of dividend profiles. However, advisors are just as culpable.

Figure 8: Bifurcation of the Investment Process

Source: Aaron Brask Capital

Source: Aaron Brask Capital

Advisors have increasingly relied on statistical models for investments and income; they have become enablers for portfolio managers by letting them maintain an unwavering focus on total returns and ignore the ramifications for income profiles. The statistical models make various assumptions about market returns, volatilities, and correlations. These parameters are then used to run simulations and estimate safe withdrawal rates[5] (SWRs) for retirees as long as the market conforms to these assumptions going forward.

These market simulations typically assume reinvestment of portfolio income but create synthetic dividends or distributions by periodically (e.g., monthly or quarterly) selling off portions of the portfolio. In other words, the concept of a natural income generated by the portfolio does not exist. Furthermore, there is no distinction between companies who do or do not pay dividends as their performance is summarized by a single total return figure.

There is one subtle but significant issue related to this synthetic dividend approach. In particular, this approach introduces an additional element of volatility to the process. Fundamentals, including dividends, are far less volatile than markets. As such, recycling dividends back into the market creates unnecessary volatility as it may be worth more or less by the time it is eventually accessed. When portions of the portfolio are sold to generate synthetic dividends, income becomes dependent on the market. In this case, one will inevitably be forced to sell at bad times (i.e., when market prices are temporarily depressed) as 100% of income is coming from the market.

Perhaps even more condemning than the additional volatility is the systematic lower returns this strategy achieves. In particular, market volatility is an enemy of the synthetic dividend approach as the penalty associated with selling portfolio holdings at below average valuations is more significant than the benefit of selling during above average periods.

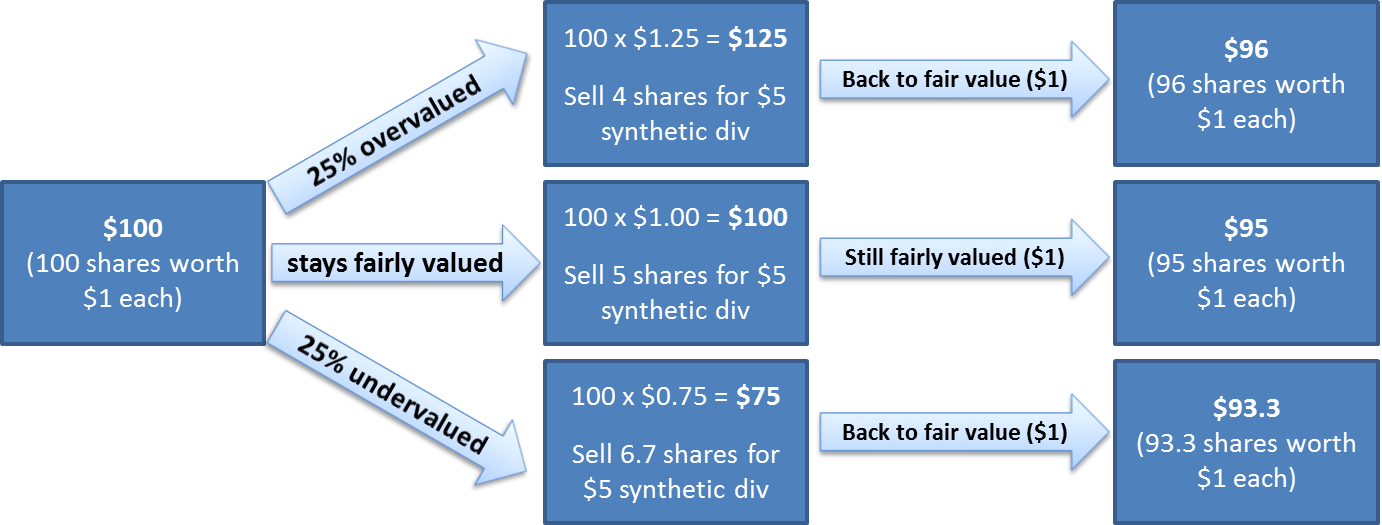

Figure 9: Recycling Natural Dividends to Generate Synthetic Dividends

Source: Aaron Brask Capital

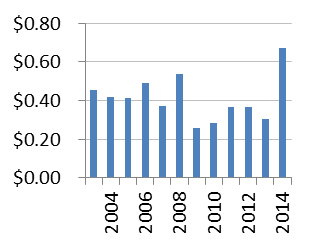

Consider, for example, a 100 $1 shares owned by an investor who needs to extract $5 each year. If the investment is overvalued by 25%, then the $5 requires selling 4 shares ($5 ÷ $1.25) from the portfolio. If the investment is undervalued by 25%, then the $5 dividend requires selling 6.7 shares ($5 ÷ $0.75) from the portfolio. Relative to a reduction by 5 shares ($5 ÷ $1.00) if the investment experienced no volatility, the downside volatility penalizes the investor an additional 1.7 shares (6.7 versus 5). This is larger than the benefit of the upside volatility as it translated into selling just one less share (4 versus 5) to cover the same $5 dividend.

Figure 10: Volatility is the Enemy of Synthetic Dividend Strategies

Source: Aaron Brask Capital

To illustrate this more generally, we simulated 100,000 30-year retirement scenarios[6] whereby an investor would either rely on (1) the dividend income generated by the stock market versus (2) taking periodic distributions of the same amount (as the dividend income). The results are clear. While it showed up only in a small fraction of the simulations, the income volatility created by synthetic dividend approach opened the door wider to the possibility of portfolio depletion – a dire situation for any investor. Even if we overlook this uncomfortable possibility, there was also a systematic reduction of returns and thus less terminal wealth. On average, the real dividend approach resulted in 7% more wealth (approximately 23bps / year) versus the statistical approach with synthetic dividends. This outperformance was the direct result of protecting income from market volatility as illustrated in our first example above.

To be fair, many have argued the synthetic income dividend approach is more efficient from a tax perspective since capital gains taxes only apply to the gain and not the entire amount of the synthetic dividend. While this is true, synthetic dividend portfolios typically include dividend payers. So the dividend taxes are already being paid on a portion of the portfolio’s income. In the case where dividend payers are specifically avoided, chances are overall returns will be lower. As we pointed out earlier, dividend paying companies have historically outperformed non-dividend paying companies. Moreover, avoiding dividend payers would also constrain the universe of opportunities – possibly avoiding higher returning investments only because they pay dividends.

Presumably, these statistical models are built this way for the sake of simplicity. However, there are academics and practitioners who explicitly support this approach[7] for other reasons. For example, they argue focusing only on dividend paying stocks creates a lack of diversification and therefore increases risk. We emphatically disagree. While this may be the logical conclusion based on academic theory, we (and like-minded investors such as Warren Buffett) believe risk is reduced when one invests in dividend-paying companies. Not only does this establish a steady baseline of income, but it also creates a natural filter for quality.

We also disagree with the more general arguments favoring the statistical approach as being simpler. Taking a certain percentage of your portfolio out as a synthetic dividend appears simple and intuitive on the surface, but it poses subtle but significant costs as we discussed above. In the case of investors with substantial wealth (e.g., category 1 or 2 in Figure 6), being able to rely on natural income instead of statistically calculated synthetic dividends can help keep the door closed to portfolio depletion, eliminate unnecessary volatility, and add to returns. Accordingly, we find this approach is much better aligned with the goals of preserving and growing wealth and offers a better balance of simplicity and transparency.

Another Quick Word on for BondsThe volatile income issue may be worse for fixed income investments. Unlike stocks, bonds have limited life spans. This forces investors to reinvest at times when rates may be significantly different than when a maturing investment was originally made. Bond managers can exacerbate this problem further by speculating across the interest rate curve. Sometimes they may concentrate allocations amongst specific maturities. Other times they may be trapped by their mandates. For example, a medium term bond fund may have to sell bonds before they expire if their maturities become too short to qualify for their medium term mandate. Selling a bond before it expires creates risk around both the reinvestment rate (investors may receive a higher or lower yield depending upon the current rates) and the reinvestment amount (bonds may not be sold at or near par). While these two risks are mathematically offsetting, the bottom line is that active management can introduce additional elements of volatility to the income profile. |

Why the Income Volatility Issue Will Persist (A Cynical Perspective)

The income volatility issue and the three primary drivers of it we highlighted above are not likely to go away. They are symptomatic of a broader phenomenon we alluded to above: the bifurcation of the investment industry between investment advisory and investment management roles. In particular, investment products and strategies have been commoditized and this trend has largely morphed the roles of advisors into sales rather than investment functions. Mutual funds started this trend by packaging the investments into funds of various flavors. Index investing has taken this to a new level with the 100s if note 1000s of new index products.

Unfortunately, this has led to some negative implications for investors. We discussed some of these concerns in our article Index Investing: Low Fees but High Costs. Many of the products and strategies based on index investing have been compromised – presumably to make them more marketable to investors – and investors end up paying the price. The issues we highlighted above are also symptoms of this trend.

The primary reason we do not expect these issues to go away is the economy of scale works well for those offering investment advisory and investment management services. Portfolio and fund managers can continue to fixate on total returns and ignore real income issues faced by investors who they will never meet. Advisors present clients with a seemingly simple SWR strategy based on sophisticated simulations and calculations they will carry out. The very hint of complexity translates into job security for them.

The advisors and portfolio/fund managers are not the only ones who support this model. Academics are attracted to investment theory and many are paid for their endorsements. The brokerage industry often provides their advisor clients with software for retirement and risk management based on these statistical models. These services are often free or paid for via soft-dollar[8] arrangements. Even the regulatory bodies get behind this model by backing and enforcing the concept of total return via conventions. Both the Uniform Prudent Investment Act (UPIA) and the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) set forth rules regarding total returns and completely ignore the income profile.

Unfortunately, marketing seemingly trumps quality as the industry continues to push these products and strategies despite their pitfalls. The truth is many advisors fully believe in the pitches they are selling; they are simply unaware of these pitfalls. While the intentions are good, their confidence is misplaced.

Solutions: How to Construct Steady Income Streams

The good news is constructing steady income streams is actually easier to implement and provides greater transparency than SWR strategies. The core strategy is to select high quality, dividend-paying companies at reasonable valuations and make income-sensitive portfolio management decisions going forward. We present an analogy using real estate to illustrate the basic strategy.

A Real Estate AnalogyMany real estate investors purchase properties for the sole purpose of generating income. Some even spend their lives building a portfolio of properties with the goal of using the income to fund their retirement. These investors focus more on the income side of the equation than the market value. With this goal in mind, real estate investments can be made and managed in a prudent manner so the end result is a steady stream of growing income. Indeed, rents typically grow with the value of the properties. Moreover, the investors may occasionally find an opportunity whereby they can sell an existing property and purchase another similar property with more rental income[9]. It is unlikely an income-focused investor would sell a rental property in order to purchase a plot of empty land even if it had strong potential for capital appreciation as this would clearly decrease the income generated by the real estate portfolio. The same logic should be applied to stock and bond portfolios. The bottom line is building a portfolio with growing income depends on the quality of the investments made and making income-sensitive decisions regarding any changes to the portfolio. |

Regardless of the type of investment, it is important to use robust metrics and judgement to identify both quality and valuation. It is worth noting many existing definitions for quality and value lack common sense and fail when put to the test of real data (see our discussion of value and growth in Index Investing: Low Fees but High Costs). We excel at quantifying quality, value, and other attributes for constructing portfolios to achieve income stability, higher returns, and lower volatility[10]. Our metrics and methodology are sensibly constructed and much more robust. Moreover, we have tested them via historical simulations with real data.

Let us go back to the original examples we used to illustrate income instability. In particular, we will work backward (worst to best) through these examples to show how our basic ingredients of quality, value, and income-sensitivity fix the income instability issues.

The worst income instability was found in the actively managed Dodge and Cox Stock Fund. As we highlighted with Driver 1, we suspect the income instability was due to a lack of income-sensitive decisions. The portfolio managers most likely focused on total return and ignored the income profile. Integrating income-sensitivity into the decision process would very likely have resulted in a smoother income profile.

Looking at the broad market where there was very little turnover, the primary culprit behind income instability was dividend cuts. In this case, upping the bar for quality would have reduced investments in riskier companies who were paying dividend but were forced to tighten their belts and cut dividends. Our third example showed the benefit of investing in higher quality companies who historically raised dividends. This fund’s dividends fell less than 5% while the broad market dividend cuts were more than 23%.

A 5% dividend cut is certainly less damaging than a 23% cut and it is entirely manageable within the context of a broader investment strategy. Indeed, it requires a much smaller buffer of near cash emergency reserves to avoid any compromises to one’s standard of living. It is worth noting the smaller cash reserve translates into larger allocations to productive income-generating investments. Notwithstanding, we like to set the bar even higher.

Even with the higher quality fund of companies with histories of paying and increasing dividends, there is room for improvement. Let us consider each of our three ingredients in the context of this fund:

Quality: While filtering companies based on their histories of paying and increasing dividends eliminates many low quality companies, we believe the bar for quality should be higher. In particular, filtering further for companies that are still growing with strong returns on capital and margins translates into more sustainable dividends and returns.

Value: This fund does not integrate a valuation metric. As long as a company has a history of paying and increasing dividends, this fund will purchase it. The example we highlighted earlier with Coca Cola illustrates the problem with ignoring valuation. Coke got caught up in the tech bubble and was trading at sky-high valuations. Its dividend yield was significantly below 1%. Other high quality companies such as 3M were trading at more reasonable valuations. Integrating valuation into the investment process can help one avoid investing in expensive companies and improve both the amount of income one receives as well as the long term returns one experiences.

Income-sensitivity: While income (i.e., dividend history) is a factor for including companies in this fund, there is no accounting for the amount of income one company generates relative to another. If a new company fulfils the historical dividend criteria, it will be included. However, if its dividend yield is lower than the fund’s yield, it will reduce the yield and income generated by the fund. Note the minor (2%) drop in dividends of our high quality fund in 2013 (Figure 1). Regardless of the valuation metric used, the relative amount of income much also be considered to ensure stable and increasing dividends at the aggregate level.

Integrating these three factors into portfolio construction and management should result in a much more stable and increasing income stream. This process relies more on fundamental trends than statistical models to generate income and thus eliminates or reduces the dependence on and risk associated with volatile markets. As such, we find this strategy is better aligned with the goals of preserving and growing wealth – especially in the case of investors with substantial means.

For those who can live off of the interest, this can translate into a simple and transparent low-maintenance strategy. Income for retirement is derived solely from the natural income of the portfolio. If one routes these dividends from the investment account to their bank account, market volatility should be of little or no concern as the steady and growing stream of dividends provides for their spending needs.

Even if one cannot live off of the interest, it is still possible leverage this strategy. For example, if dividends alone do not cover one’s expenses, they may convert some of their portfolio into an income stream via an annuity. This portion of the portfolio (both principal and future dividends) will be converted into a fixed (or inflation adjusted) income stream. The point is to effectively sacrifice enough principal so that the balance of the expenses after the annuity stream can be covered by the dividends from the rest of the portfolio.

For example, consider a 65 year-old retiree with $5 million in savings and an annual budget of $250k. This budget is 5% of his wealth and would thus not be covered by a 3% dividend yield. If he allocates half of his portfolio ($2.5m) to an inflation-adjusted annuity paying him 8% of the invested value per year until he passes, this will provide for $200k (8% x $2.5m) of his budget. With the other half of his portfolio invested in high-quality companies currently paying a current yield of 3%, then this will provide another $75k (3% x $2.5m) of income that should grow through time. The total income generated by this strategy will be $275k and thus cover his budget with some buffer. This example is solely for illustrative purposes and the numbers do not represent real market rates. Moreover, while we did not use one in this example, we strongly recommend integrating a cash reserve as part of the overall asset allocation strategy.

Growth (non-income) StrategiesWhile this discussion has been predicated on income-focused investors, the quality and value factors also apply to growth-oriented investment strategies. The key difference would be the balance between the two factors. In an income-focused strategy like we described above, the growth of a company’s dividends and other fundamentals are the primary driver of the portfolio returns. A more aggressive growth strategy would involve targeting higher returns by capturing increases in valuations as well. These strategies can be particularly effective in tax deferred investment accounts (e.g., IRAs) where capital gains are not taxed on each sell. |

Conclusions

This article demonstrated how and why the statistically-based SWR strategies introduce unnecessary risk and performance issues for investors. Unfortunately, we suspect most advisors advocating SWR strategies are unaware of these issues – just as we suspect many are unaware of the issues with index investing. The industry brushes much complexity under the rug and to facilitate the sales process. However, this façade of simplicity comes at a steep cost as index-based SWR strategies typically result in riskier and more volatile income streams and can detract from returns by more than 2-3% per year.

It is important for investors to select advisors who can avoid the pitfalls inherent in these approaches and provide more robust strategies to provide stable income without compromising capital preservation or growth. Increased focus on income and selection of high quality funds or securities are critical for these goals. While we believe the performance benefits alone should make a strong case for our natural income approach, its simplicity and transparency can provide investors with a superior level of comfort as well.

About Aaron Brask CapitalMany financial companies make the claim, but our firm is truly different – both in structure and spirit. We are structured as an independent, fee-only registered investment advisor. That means we do not promote any particular products and cannot receive commissions from third parties. In addition to holding us to a fiduciary standard, this structure further removes monetary conflicts of interests and aligns our interests with those of our clients. In terms of spirit, Aaron Brask Capital embodies the ethics, discipline, and expertise of its founder, Aaron Brask. In particular, his analytical background and experience working with some of the most affluent families around the globe have been critical in helping him formulate investment strategies that deliver performance and comfort to his clients. We continually strive to demonstrate our loyalty and value to our clients so they know their financial affairs are being handled with the care and expertise they deserve. |

Disclaimer

|

- We used the NASDAQ Dividend Achievers Select Index as a proxy for high-quality dividend paying companies. ↑

- We used the S&P 500 index as a proxy for the broad US equity market. ↑

- We used the Dodge & Cox Stock Fund given its 50 year track record of outperforming the broad market. ↑

- This also assumes the bond is not called back by the borrower. ↑

- A safe withdrawal rate (SWR) is defined as the percentage of an initial investment that can safely be withdrawn per year and not lead to portfolio depletion. The rate will typically grow (as a percentage of the initial investment) through time to account for inflation. ↑

- Our simulation assumed a high quality stock market portfolio with average total returns of 6%, a starting dividend yield of 3%, market volatility of 25%, and average price/book valuation of 5. ↑

- Famed academic Kenneth French is an outspoken advocate of synthetic dividends. ↑

- Soft dollars refer to the provision of data, software, and other services to asset managers from their brokers. They are essentially kickbacks to the asset managers that encourage them to execute client transactions through their brokerage. ↑

- While we are not experts and investors should consult relevant legal and tax professionals, transactions like this may be done via a 1031 exchange whereby the IRS does not tax capital gains on the property being sold. ↑

- While academic theory links higher returns to higher risk, we side with Warren Buffett and other legendary investors who understand value investing can both increase returns and lower volatility. Indeed, paying less for a given company allows for more upside potential and reduces the amount by which the share price can fall. ↑